(October 12, 2021) With a new season of hockey starting today, we thought we’d give a shout out to the top Indigenous Hockey Players in the NHL. With the help of Trege Wilson who contributes to the The Hockey Writers, we’re featuring the best of the best of Indigenous hockey players in the NHL.

Since the beginning of the game in 1917, 7623 players have been on an NHL team, about 80 of whom have been Indigenous. For a full list of Indigenous players, check out Native Hockey.

Hockey is played in community rinks or any piece of ice that can be skated on in villages, towns, and cities on reserve and off.

“I think we as First Nations people are probably some of the biggest supporters of hockey across Canada,” said Reggie Leach, the NHL.’s first Indigenous superstar told Stephen Smith in the New York Times in 2018. Leach, who is Ojibwe, spent 13 seasons in the N.H.L., mostly with the Philadelphia Flyers, winning a Stanley Cup in 1975.

The first recorded Treaty Indigenous player was Fred Sasakamoose, who played 11 games with the Chicago Black Hawks during the 1953-54 season. He writes about his hockey career and being taken away from his family to go to Indian Residential School when he was seven years old in his memoir, Call Me Indian, published in May 2021.

Yet, it would be remiss if we don’t acknowledge the contribution of George Armstrong.

Between 1950 and 1971, Armstrong played 21 seasons with the Toronto Maple Leafs and was captain for 13 seasons. He scored the final goal of the NHL’s “Original Six” era as Toronto won the 1967 Stanley Cup.

But “Armstrong’s grandparents were trappers – an Algonquin mother and an Irish father – they did not live on reserve. And because Armstrong’s mother, an Algonquin woman who described her work in Falconbridge as “washing the floors for the bigshots,” married a non-Indigenous man — an Irishman who worked at the mine — she fell victim to the loss of her status, due to the gendered rules of the Indian Act.” according to Jenny Lamothe, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, sudbury.com. Armstrong passed away in January 2021 at the age of 90.

Carey Price

Carey Price’s father Jerry Price—a former Philadelphia Flyers draft pick who made goalie masks in his spare time—would set up the flood lights, shovel off a portion of the creek that ran through the land where he grew up, siphon water from beneath the ice and flood the surface to create a makeshift rink. It was on that ice that his three-year-old son, Carey, learned to skate. He played organized hockey in Williams Lake over five hours and 320 kilometres away by car. Having to make the ten-hour round trip three days a week, Carey’s father acquired a small bush plane to fly him to practice and games.

At the end of last season, he’d played 707 games with 360 wins, 257 losses, 79 ties and 49 shut outs.

Price will not be starting the 2021/2022 instead seeking treatment for mental health issues. His decision has been lauded by many in the NHL. Price’s former teammate, Dale Weise, offered him a salute on Twitter. “The amount of people that will be helped by a guy of this magnitude coming out and saying he needs help will be astronomical,” Weise wrote. “People including myself have no idea what it’s like to be Carey Price. The weight and pressure he has had to carry for so long is unimaginable and the way he has done it has been incredible. He is one of the best teammates and people I have ever played with.”

T.J. Oshie

His father who suffered from early onset Alzheimer’s passed away in May 2021 at the age of 56.

Theoren “Theo” Fleury

”Theo Fleury will bring some additional scoring punch to our hockey club and much more. For many years in this league, he has been a proven leader and a great playoff performer,” Coach Bob Hartley said, according to the New York Times. During his career Fleury recorded 90+ points four times, and 100+ points twice and twice represented Canada at the Winter Olympics, winning a gold medal in 2002, he reportedly battled drug and alcohol addictions.

His grandmother Mary was Cree and he grew up with a Métis heritage. Seeing his talent, his community sent raised money to send young Fleury to hockey school in Brandon, Manitoba. There he met Graham James who promised to recruit him to junior hockey when he was old enough. In 2009, Fleury wrote his autobiography in which he explained he had been sexually abuse by Graham James over a period of two years. He also shared that he failed 13 consecutive drug tests while with the New York Rangers, but they didn’t want to suspend him because he was a top goal scorer. Today, Fleury is a motivational speaker about trauma, mental health and addiction.

Reggie Leach

His mother, Jessie Ackabee, was from Eagle Lake First Nation, an Ojibwe community in northwestern Ontario. Raised by his paternal grandparents, Leach played for Riverton at the Bantam, Midget and Juvenile levels, In 1965–66, Leach played for a Junior B team in Lashburn, Saskatchewan, but returned to Riverton when he became homesick. He played for the Flin Flon Bombers during the 1966–67 season and met Bobby Clarke, the son of a Flin Flon Miner. The Flin Flon team became part of the Western Canadian Junior Hockey League in the 1968-69 season. After being drafted by the Boston Bruins in the 1970-71 season, and spending two seasons of unproductive time on the bench, he was dealt to the California Golden Seals and then, finally, to the Philadelphia Flyers, where his friend Bobby Clarke was captain.

Leach ended his NHL career with the Detroit Red Wings in the 1982–83 season and currently resides at Aundeck Omni Kaning First Nation, near Little Current, Ontario.

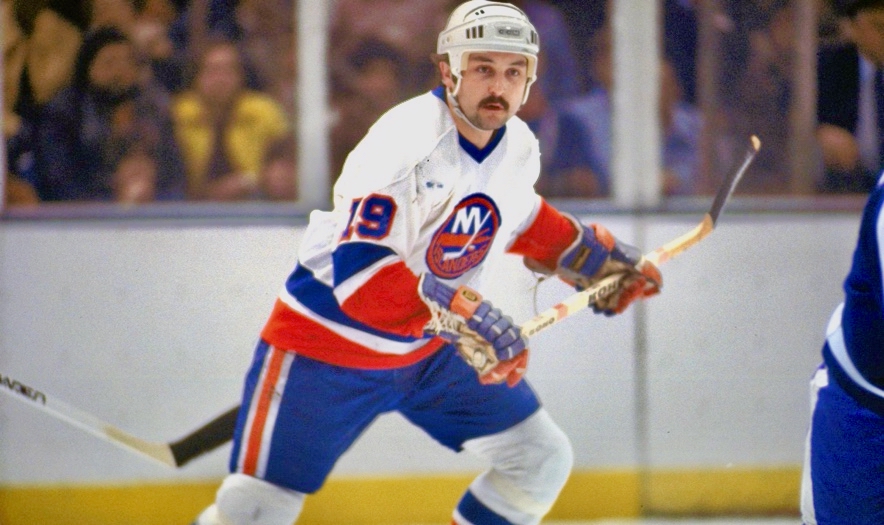

Bryan Trottier

He grew up in Val Marie, Saskatchewan about 30 km from the American border. He has Metis, Cree and Chippewa ancestry. His father crafted an ice rink for him and his brothers out trees branches and left over material from beaver dams. He could sometimes skate almost 20 km on Frenchman Creek to town over rough stretches with twigs and rocks in frozen in the ice.

According to nhl.com, Trottier was selected by the Islanders in the second round (No. 22) of the 1974 NHL Draft. Trottier remembers being in a makeshift locker room in training camp with 60 rookies, then 50, then 40. Cuts kept coming, and Trottier was still around. Then there were 20 rookies, then 10, then five. He received no feedback on his play at all. “They didn’t say one word to me the entire camp,” Trottier said. But, according to nhl.com, when the season finally started, Trottier found himself playing center on a line between Clark Gillies and Billy Harris. The Islanders tied the Kansas City Scouts 1-1 in Trottier’s first game. In Game 2, he had a hat trick and five points. Trottier now talks to Indigenous children about leadership.

Related reading

Fred Sasakamoose: Call Me Indian October 12, 2021