by Katherine Verhagen Rodis (October 10, 2019)

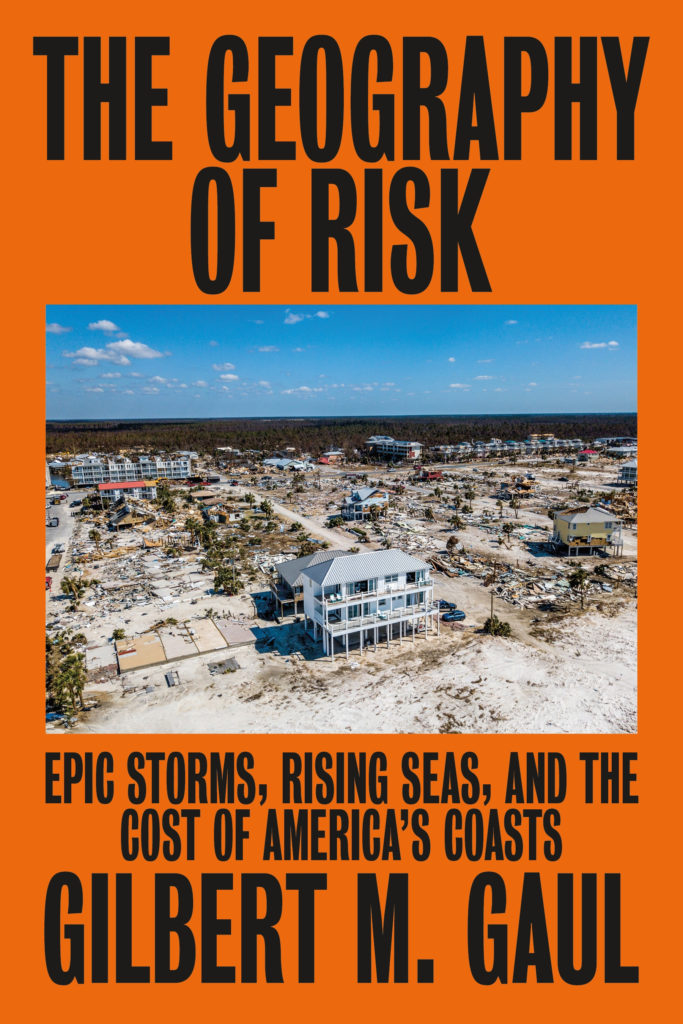

The Geography of Risk: Epic Storms, Rising Seas, and the Cost of America’s Coasts by Gilbert M. Gaul, Sarah Crichton Books, September 3, 2019, 304 pp, $38.00

Tropical storms are increasing in their intensity, causing more devastation in their path. Gilbert M. Gaul, in his recent book, The Geography of Risk (2019), stresses that

Many of the hurricanes of recent years have intensified at alarming rates, strengthening from relatively small, even harmless storms into meteorological nightmares. [As recent examples,] Both Florence and Michael exploded from tropical depressions into major hurricanes in three days or less.”

Gilbert Gaul has twice won the Pulitzer Prize and has been shortlisted for the prize four times. For more than thirty-five years, he worked as a journalist for The Washington Post, The Philadelphia Inquirer, and other newspapers.

He has reported on non-profit organizations, homeland security, and Medicare. He takes us along a journey to determine how and why the American federal government transitioned to paying for up to 5% of hurricane-inflicted damage made to residential properties half a century ago to now between 70% to a 100%. In an interview with NPR, Gaul estimates that the total damage caused by hurricanes along the Atlantic U.S. coastline is equal to “three quarters of a trillion dollars in damage just in the last two decades.”

Gaul sits in the figurative eye of the storm, a place of deceptive calm. Trained as an investigative journalist, Gaul will not give you a blueprint to mitigate climate disasters or how to engage in political action to avert climate crisis.

Instead, he examines the rise of a deeply flawed system of “disaster capitalism.” It’s a system that rewards exponential real estate growth along America’s Atlantic coastlines, entailing a predictable cycle of destruction, federal relief, and rebuilding.

Though opinions diverge about how climate change affects the frequency of tropical storms, it is overwhelmingly apparent that there is a direct correlation between increased human carbon offsets and increased hurricane intensity.

Higher sea levels and warmer sea temperatures equal higher precipitation, explain members of the U.S.-based Environmental Defense Fund.

“Evaporation intensifies as temperatures rise, increasing the amount of water vapor that storms pull into their systems as they travel across warm oceans. That makes for higher rainfall and more flooding when they hit land.”

And higher precipitation means higher devastation producing what Gaul calls “rain bombs” dropped during torrential storms.

As hurricane victims are attacked from above by torrential rains, it is “storm surges” that often pose a bigger threat. Sudden and abnormal rises in water levels brought on by wind and air pressure changes are “the number one killer in hurricanes.”

While we may think we have it safer the further we live inland and the further away from the equator, the Canadian government warns us that a storm surge can often “accompany hurricanes, high winds or very intense winter storms,” especially around large lakes (like the Great Lakes) in addition to all coastal areas of Canada. If you need a reminder of what sudden flash-flood devastation can look like, check out this footage of Hurricane Dorian’s storm surges affecting people in the Bahamas.

Americans have built $3 trillion worth of property in some of the riskiest places on earth: barrier islands and coastal floodplains. They have done so comforted by subsidies, tax breaks, loans, and flood insurance (often provided by government agencies). All with the often-justified assumption that someone will bail them out in times of great upheaval, usually the federal government on behalf of the public taxpayer.

According to C2ES, the Center for Climate Change and Energy Solutions, an important driver of the increased cost of hurricanes is increasing development in coastal areas. American coastal populations increased by nearly 35 million people between 1970 and 2010. Inland, developers take advantage of low-cost land near flood-prone marshes and creeks.

There have been times state and federal agencies have tried, but failed, to reign in developers and decelerate coastal development. Yet, as coastal geologist Al Hine stresses in Gaul’s Geography of Risk, “the problem comes back to politics. Decisions are made in terms of election cycles, and that discourages politicians from taking steps to reduce long-term vulnerability.”

In an administration that doesn’t believe in climate change and sea-level rise, “it creates a culture of denial and cheap fixes become the norm, instead of real adaptation.” As Gaul cycles through multiple towns along the American Atlantic coastal shoreline, the hurricanes keep getting larger, the damage more destructive and the solutions less sustainable in the long-term.

Gaul doesn’t believe in overnight change but hopes that his book sparks a serious conversation that’s long overdue. It’s time to stop building on sand and time to take rising seas and epic storms seriously. Ignoring them is a risk with too great a cost.

Katherine Verhagen Rodis is a proud member of the Canadian Association of Gift Planners, with interests in foundation, major and planned giving. She’s a former teacher and academic, is #LGBTQ+ and #neurodiverse, (she/her). @kverhagenrodis