by Roger Ali, June 11, 2021

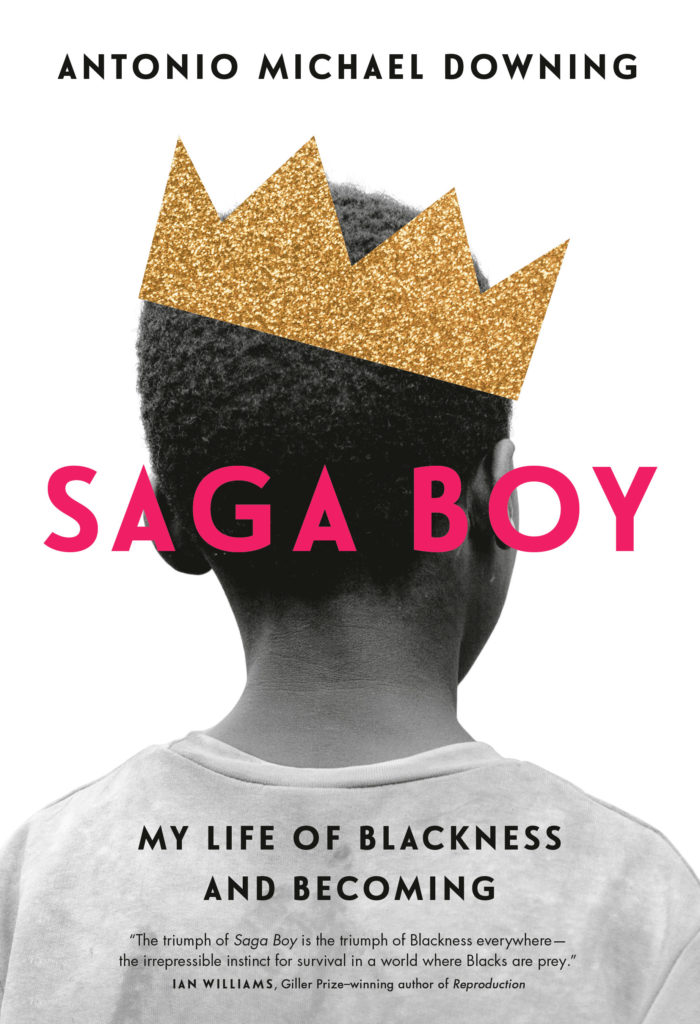

Saga Boy: My Life of Blackness and Becoming, Antonio Michael Downing, PenguinRandomHouse Canada, January 29, 2021, 334 pp., $23.21

Saga Boy is a memoir of love, loss, and pain, of self-actualization and acceptance. It is a beautiful, raw story about Antonio Michael Downing’s life-long search for his black identity as he approaches each stage of life with vulnerability and courage. In the four-part memoir, with each act referencing a specific period of his life, he masks as a different person, his alter egos—Tony, Michael, Mic Dainjah, Molasses and John Orpheus.

As an immigrant from Trinidad myself, the deeply personal experiences took me through a winding, heartbreaking journey along familiar and unfamiliar settings.

In Act One, Tony and his brother Junior are growing up deep in the rainforests of southern Trinidad under the care of Miss Excelly, his beloved grandmother, who he affectionately calls mama. She is the only parent he knew. Al and Gloria, his actual parents, are just a rumour, completely unknown to him.

Through words and songs, Miss Excelly gives young Tony the two great lessons that end up shaping him. And she is no exception to the many Caribbean women are steeped in religion and faithful to God. Tony learned to read by studying the King James Bible. Reading the bible was part of Miss Excelly’s daily ritual and her salvation. When her sight became poor, Tony read her the Proverbs and Psalms. As she passed away, Tony was there to witness her last breath. He was eleven years old, his life abruptly changing when he and Junior left the fields of sugar cane planted amidst the thick tropical forest known as Monkeytown to live with his Aunt Joan in Canada.

In Act Two, Tony’s alter-ego is Michael. And it is Michael who arrives at a tiny place called Wabigoon, an Indigenous community in Northern Ontario in the dead of winter. It’s a rare spot for a new immigrant to begin life in Canada. He describes his surroundings as a new kind of bush, dead, empty and buried in snow and ice. It starkly contrasts with my own arrival from Trinidad to Hamilton in the mid-eighties.

Michael’s Aunt Joan is a Seventh-day Adventist Christian of stature and strength. She loves the Lord and showers Michael with her beliefs, but Michael struggles with the isolation. He’s not fitting in with his classmates, the white settlers, or the Indigenous community. But a turning point comes when he attends a PowWow and begins to understand and acknowledge that Indigenous people were very much victims of colonialism and racism, just as he was, yet they still had their power and strength and were part of the land. It’s a realization that stays with him.

Act Three begins with an emotional adventure that includes Michael and Junior meeting and moving in with his dad and his dad’s new wife, a former call girl named Hailey. Michael learns his dad, like his father before him, is a Saga Boy, a Trinidadian playboy, addicted to escapism, attention, and sex. He decides to follow in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps, claiming the Saga Boy legacy proudly, describing it as a way of responding to the life he was given, a way for him to understand himself, his parents, and grandparents.

Here, I felt I was travelling alongside Michael in the deep personal experiences he encounters as his life takes a series of twists and turns. The beauty of Trinidad and love of Miss Excelly seem so far away from his loneliness and manic lifestyle. He retreats into writing words and songs, connecting with people who just show up in his life, people who end up being his chosen family, and who ultimately have his back.

In Act Four, our author is transformed once again. Meet Mic Dainjah, a newly minted Canadian and the lead singer of Jen Militia, whose day job is working as a sales associate at Blackberry. He sees Al and his mother Gloria and wishes they would take care of him like his friends’ parents sacrifice to help their kids.

“But they were broken as I was, and that kind of caring was just not in their nature,” he says.

He cuts ties so he can heal and move on with his life. He seeks out anger management therapy to stop harmful behaviour for which he’s feeling shame and remorse. It’s a powerful lesson about the need to learn from our past, to accept, forgive and love.

In this memoir, Downing succeeds in evoking the inherent imperfection of families and friends, and how our personal history can manifest in unusual ways.

Through Tony, Michael, Mic Dainjah, as well as a soul preacher named Molasses, and a persona named John Orpheus, from the Orfeu Negro (Black Orpheus), Downing found the clue for the enigma of his life. He also brought a new level understanding of playing Mas to me. Mas is part of Trinidad’s Carnival where participants dress in colourful, elaborate costumes and dance to soca, calypso, metal music, expressing the inexpressible through costume and music.

Finally, I understand Downing’s journey and the clue he had discovered.

“Becoming someone else was my drug of choice. My personas were the cure for my self-loathing.”

The book opens and ends the book with “The Queen designed my brain.”

Born when Trinidad was a British colony, the Queen’s picture hovered over Downing every day at school. She was the framework for his thoughts. He learned to read by studying the King James Bible. By the end of the book, Queen Elizabeth transforms into Miss Excelly, Gloria, and Aunt Joan, Caribbean women on the opposite end of the hierarchy, poor with little or no education. But their resilience and strength also shaped his life and character, the course he travelled, and where in the end he became the person he always was.

In the words of Oscar Wilde, “Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.”

Roger D. Ali, MBA, C. Dir., is a recognized nonprofit leader and a book reviewer of The Charity Report since 2019 @fundraiseroger

Also reviewed by Roger Ali

Latest from André Picard: Neglected No More is a plea to stop dehumanizing eldersCovid-19: The Pandemic that Never Should Have Happened November 12, 2020

Diversity Inc: How the diversity industry is thriving, even if diversity itself is notSeptember 20, 2020

Rising Tides: Part of the literary response to climate change July 17, 2020