by Gail Picco October 12, 2021

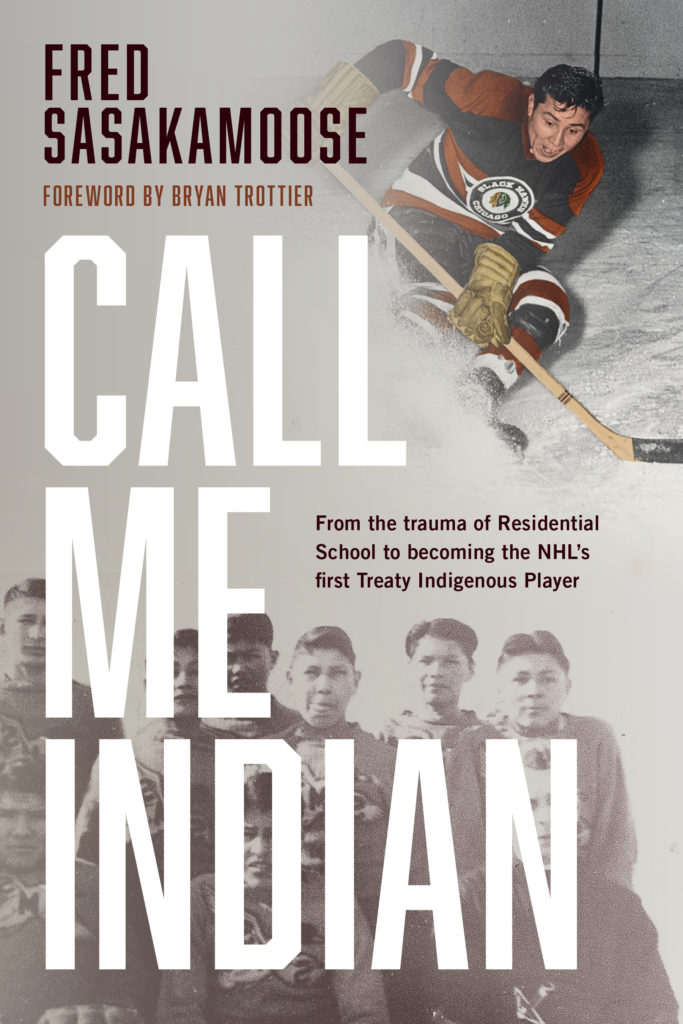

Call Me Indian: From the Trauma of Residential School to Becoming the NHL’s First Treaty Indigenous Player, Fred Sasakamoose, forward by Bryan Trottier, Viking Canada, May 18, 2021, 288 pp., $23.18

(October 12, 2021) Fred Sasakamoose’s Call Me Indian is a story worth telling, beautifully rendered, and artfully told. It’s a family saga—the influence on Sasakamoose of his moosum, his grandpa, the bright cheerfulness of his mother, her inventive in the ways of getting things done while his father was away, logging or working the trapline, and her willingness to speak truth to Sasakamoose later in his life, when he needed it. Sasakamoose’s descriptions of his siblings, and his own wife and children leap off the page, and we are invited to pull up a chair to join them.

There are many Sasakmooses, a family descended from Ahtahkakoop, the Cree chief that claimed the land Fred Sasakamoose lived on, then called Sandy Lake, as their own. His family was sprawling, but he was the only one who played hockey well enough to make it into the NHL to play for the Chicago Blackhawks in their 1955/56 season. He was the first Treaty Indigenous player to do so.

Born on Christmas Day in 1933, the first seven years of Sasakamoose’s life were lived within the closeness of his family, in a home “full of song, dance, and tradition. It was full of wonder and mystery. It was full of family, love and community,” he writes. They spoke Cree at home, travelled miles by sled with his mother to visit family, Sasakamoose was nurtured by his moosum, a man who couldn’t hear or speak, but communicated using hand gestures, a man of whom Sasakamoose writes,

“Moosum and I didn’t need to talk to understand each other. He would look over at me and smile, and I immediately knew what he was thinking. We’d often go for long walks together. He’d hold my hand or rest his palm on my back, and with each footstep I felt as if what was on his mind was floating through the air to me.”

Moosum even taught Sasakamoose to skate. Then one day when he was seven years old, Sasakamoose writes that a “huge canvas-covered grain truck appeared in front of our little cabin.” The Indian agent, an RCMP officer and a priest got out and the priest talked to his mother. The scene is mayhem as Sasakamoose’s father comes from around the back of the cabin to see what’s going on. His brother Frank is grabbed by one of the men. Sasakamoose hides behind his moosum. The men push grandpa onto the ground and hoist Sasakamoose into the back of the truck, to join a crush of crying children. The last thing Sasakamoose sees before the truck drives off is his “moosum, lying on the ground, shaking and crying.”

For the next seven years, Sasakamoose attended an Indian residential school at Duck Lake, Saskatchewan, a place where cruelty did seem to be the point, were children we not schooled, but used as labour, fed an inadequate diet, had their illnesses go unchecked, where Sasakamoose was raped by a gang of other boys while a priest stood with his back turned. Many children became sick and died.

Yet “with all the misery at that school, the best relief for me was always sports. Soccer, softball, basketball. And more than anything else—hockey.”

He worked hard at hockey practice coached by one of the priests who couldn’t play the game himself, but knew a lot about it according to Sasakamoose. And Sasakamoose’s talent began to show. He played for the Duck Lake Ice hockey team, and when he was 16 was scouted by the Moose Jaw Canucks, who played in the Western Canada Junior Hockey League. After scoring 31 goals during the 1953–54 season he was named the league’s most valuable player. In 1955, Sasakamoose was drafted by the Chicago Blackhawks and played 11 games for the team.

Following his stint with the Black Hawks, Sasakamoose writes that for the next 10 years, he “followed the money, jumping from team to team, from league to league. I kept playing even when my club was finished for the season. Other teams in other leagues often tapped me to help them out in the playoffs.”

In the early 1960s, while he was playing in northern Saskatchewan towns, he was also working on the founding of the Northern Indian Hockey League, and his work in promoting hockey was a catalyst for the construction of arenas in communities in northern Saskatchewan.

But by 1969, after a season with the Prince Albert Barons, Fred Sasakamoose decided he was done. “I packed up my gear and headed for Sandy Lake. I knew I wouldn’t be back. I was going home for good.”

Sasakamoose played hard on and off the ice but says he didn’t always appreciate his children. “In the spring and summer, I still ran the rec programs on the reserve, spending hours with all the local kids, not just my own. And then when I did spend some time at home, I could be really hard on my kids, especially the older ones.”

He served as a band councillor of the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation for 35 years and was approached by the former band leader Allan Ahenakew to run for chief in 1980—with a couple of provisos. Sasakamoose recounts the meeting:

“I have a few things to tell you, Fred,” Allan said, after a moment of silence. “To serve your people, you have to avoid drink. You have to go to church. You have to be a role model. Show them a brighter life. We are poor, but poor is nothing. It’s what you give that counts.”

Sasakamoose writes, “I knew he was right. I needed to change the direction I was going. I’d been worrying for years that I’d failed by people. I needed to stop thinking the only way I could be a role model was as a hockey player. I needed to be a better man to be a good leader. A better husband, a better father, a better grandfather … And I need to embrace my heritage more strongly. I’d also work on my Cree language so I could once again speak as fluently as Allan did.”

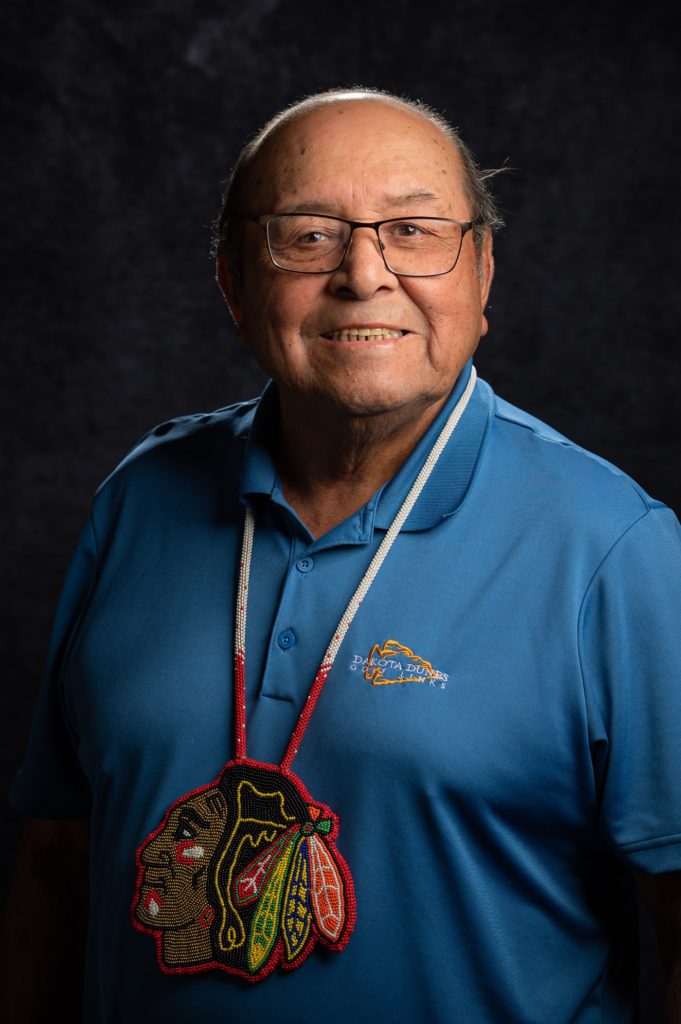

And Fred Sasakamoose did all those things. While gathering awards for his contribution to his community and to hockey, he was successful in his quest to as become as fluent in Cree as he was before he was taken away to Indian residential school. The book happily bounces back and forth between English and Cree, the reader enriched by the simple sight of an Indigenous language featured in Canadian mainstream publishing.

Sasakamoose’s experience at Indian residential school hangs over the book, just as it did in his life. How any child can survive the treatment dealt out to them in such settings beggars the imagination.

But Sasakamoose’s story telling is sure and steady. We stop at every stream we need to contemplate, look up at each mountain that needs to be considered, gaze at the part of landscape that needs to be mulled over, use the words we have, to describe what we see.

Fred Sasakamoose never saw his finished book. He died from the complications of covid on November 20, 2020, four days after he was admitted to Prince Albert Hospital. He is buried at the Ahtahkakoop First Nation Cemetery in Ahtakhakoop, Saskatchewan.

Call Me Indian is a gift from a guide who knew what we need to know.

More reviews by Gail Picco

#BlackinSchool: How school reinforces racism September 12, 2021

Likeness by David Macfarlane: A father’s thoughts of a future without his son July 26, 2021

Sylvia Olsen Unravelling Canada: Pulling at the stitches of Canadian history June 22, 2021

A Girl Called Echo: A Resounding Messenger of Métis History May 10, 2021

David Love: Thoughts of an Environmental Fundraiser April 30, 2021

What Bears Teach Us: The push and pull of co-existence December 8, 2020