(April 22, 2020) On March 11th, from its headquarters in Geneva, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic.The declaration, and its implications, exploded with a domino effect across the rest of the world.

As the shockwave hit the east coast of Canada, the Artistic Fraud theatre in St. John’s was hours away from taking their original play Between Breaths on the road to B.C., New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. Between Breaths is a retelling of the story of Dr. Jon Lien who pioneered techniques for rescuing whales trapped in fishing nets.

Photo: Ritchie Perez

The troupe was set to fly to B.C. on Saturday, March 14th. Many of the tour’s expenses had already been paid. Airfare had been booked, and accommodations and vehicles had been reserved. Freight made up of sets, props and costumes was already in B.C. The artists of the troupe had been given their two-week tour per diem cheques.

“I’m just so grateful we weren’t already on the road. That would have been very hard,” says, Patrick Foran, Artistic Fraud producer.

Louise Moyes is a performance artist. She creates what she calls docudances. In 2018, she created a docudance about her neighbourhood on Long’s Hill in St. John’s. It’s a curved road that cuts a swath towards the harbour from mid-town at the intersection of Parade Street and Harvey Road to downtown at Gower Street and the famous drinking strip, George Street.

My neighbour says “If you put a pin in the middle of Long’s Hill and drew a half-a-kilometre radius you would hit every walk of life, every echelon of society, every culture that we have in St. John’s.” Moyes told CBC Radio’s St. John’s Morning Show in October 2018.

Her outdoor docudance about Long’s Hill encompassed 200 years of the neighbourhood’s history and uncovered a vibrancy of stories about an area that’s often branded as crime ridden. The idea was to take people for a walking tour of the area with a stop or two along the way for a dance.

Photo: Justin Hall

On Tuesday, March 16, 2020 Moyes was in the dance studio with her frequent collaborator, multidisciplinary artist, Lisa Porter. They were working on a duet, joking about the impossibility of social distancing while performing their piece, going to the point of getting a colleague to take a picture of them at either end of the studio.

“But by one o’clock, we weren’t laughing anymore,” says Moyes. The provincial government had just issued a public health order that prohibited gatherings of more than five people. Businesses except essential services would close. Funerals, visitations and wakes would be disallowed.

“That put a stop to art making,” says Moyes. “Most of my work has been solo, but nothing is really solo. Performance artists were immediately affected.”

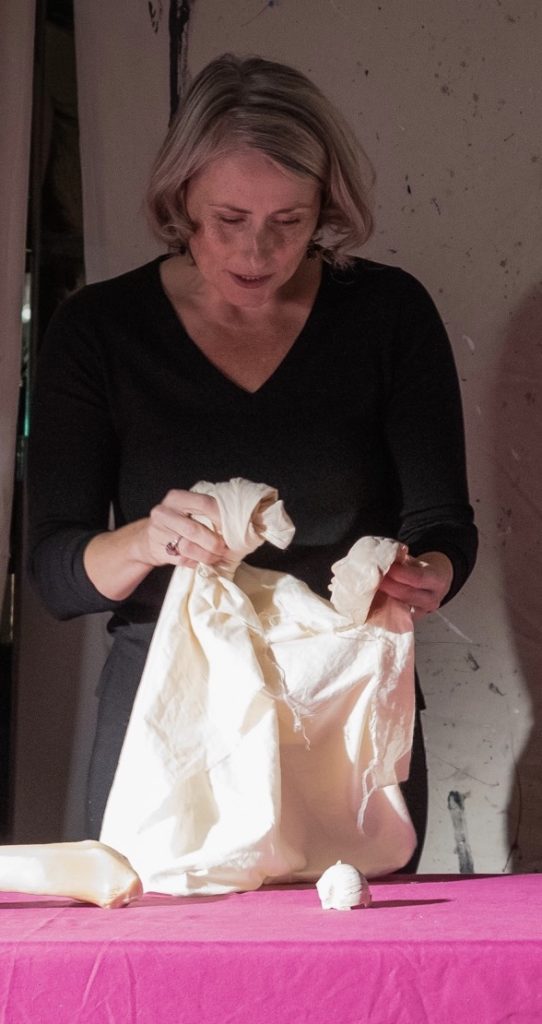

Tara Manuel is a celebrated puppetry artist, who spent several years working off the island as an actress.

“I turned away from a career as an actress,” she says, “because I felt I was always in a weakened position where older men were trying to manipulate me. Then I got pregnant and knew I was coming back to Newfoundland to raise the baby. I told my husband that he could come with me or not. He did come.”

Photo: Reg Higgins

Manuel now lives within a stone’s throw of the school she and her 13 brothers and sisters attended in Corner Brook, Newfoundland.

When her sons were young, she wrote two books. When one of them got sick and was convalescing at home, she did a puppet show version of St. George and the Dragon.

“I ended up taking that show to 60 communities through Newfoundland and Labrador. My husband made the stage and props to fit in the back of a Mazda. I had been going to rural schools, teaching drama and been asked what’s theatre, miss?”

Puppets help “express the inexpressible,” Manuel says.

When the public health order came down, she was scheduled to do a tour of her show The Lady of the Falls in nine schools around the western region of the island. The Lady of the Falls tells the story of a young girl’s heroic journey upriver to meet the feared protector of the river and forest.

Cheryl Hickman is the award-winning founder, general director and artistic director of Opera on the Avalon, a company that commissions new operatic works based on Newfoundland and Labrador history. Prior to becoming an arts administrator, Hickman was a critically acclaimed soprano who sang with New York City Opera, the Canadian Opera Company and many others.

“We were lucky. We were in pre-production for two shows, including Ours, at the National Arts Centre [in Ottawa] and could pull back quickly,” she says.

“There is a lot of fear right now. Artists don’t make a lot of money. In Newfoundland, the average income for an artist is $27,000 a year. It’s difficult at the best of times, but as a cultural sector, we cannot let what is happening now happen again. Artists are essential to society. They have to be supported like they do in Ireland where artists don’t pay taxes.”

Art is a great source of pride of place Hickman says pointing to art incubation projects in rural communities such as Bonavista, Port Rexton and Fogo Island.

Art and artists are a huge economic driver,” says Hickman. “When you think about the impact of artists … what are people sharing now? Music and poetry.”

“I’ve been a theatre producer for eight years,” says Foran, “and I felt like I was just getting good at all that—finding venues, marketing, managing people and productions, everything a producer does—and, overnight, none of those skills are what I need.”

Like every arts manager, he says he’s “going to school” in things like insurance policies, the details of grant acceptance policy, and eligibility for the federal payroll subsidy.

“The arts councils are trying to help, and it’s appreciated,” he says. Because Arts NL had an increase in funding from the provincial government, Artistic Fraud got an increase in funding and the Canada Council for the Arts is front-end loading some of their grants.

“It was great to see the Prime Minister address artists. It’s a recognition that within Newfoundland and Labrador, there won’t be much of a tourist season this summer.”

But Foran and the artists of Artistic Fraud are meeting on a daily basis, processing what’s going and thinking about adapting their work.

“For sure when the curtain lifts, there will be new work. We are supporting the creation of new work now and finding a way to work with our artists that also meets the public health guidelines.”

“We feel a commitment to our fellow artists and to support the community. In these communities, they know when the theatres are busy, they’re busy too. But we take our cues from [Chief Medical Officer] Dr. Janice Fitzgerald.”

Opera on the Avalon has commissioned a new opera based on the book February by Lisa Moore which will feature female composers. The book February is based on the sinking of the Ocean Ranger oil rig in February 1982.

“While other organizations can offer programs online, because of a variety of factors, it’s hard to get a full length Canadian opera online,” says Hickman. “But we are working a new project that could work and still follow the public health guidelines, with artists and filmmakers performing and shooting in prominent locations across the island.”

The new project is called The Rock Performs and photographer David Howells will be involved.

If it’s grocery stores that are open, then that’s where we will display our work,” vows Hickman. “We are innovative people because we are used to disaster at every turn.”

“The fact that we are just coming out of Snowmageddon, where people couldn’t leave the house for eight days, really set the stage for this [pandemic response], I think,” said Louise Moyes.

Through her docudance about Long’s Hill, she got to know more about the people in her neighbourhood.

“The individualism, the Netflix, the driving everywhere is happening here too,” she says. “On Long’s Hill, we’ve got oil executives and sex trade workers door to door. Part of the Long’s Hill piece was to try to get the neighbourhood to know itself better.”

During Snowmageddon, it became apparent to Moyes that a lot of her neighbours were suffering.

“I saw a sad-looking man on the street walking downtown to where the supermarket was supposed to be open, and then I saw him coming back still looking sad. I went out to see how he was. He had no food, and said he was mortified.”

She and her friends started knocking on doors and found many people who had nothing. Within a few days, and with the help of donations from other neighbours, they had fed 80 people. Donations of money and food came in quickly and went out to the people who needed it just as quickly. The citywide experience exposed the depth of the poverty in St. John’s where 30% of the population is now believed to be food insecure. By the end of February, Moyes was still heavily involved.

We are so lucky as artists. We can work away on something without knowing why or where we’re going,” she said.

“I’ve spent 25 or 30 years doing dance pieces about social justice, but with the pandemic, it has evolved into something else. When it became clear we were going into a public health emergency, I knew it was going to be worse than Snowmageddon.”

Moyes and her colleagues have formed a group now called Food for Now: Friends of Community Centres. They began working with community centres, food security organizations, and all levels of government, as well as having conversations about food insecurity from St. John’s to Nain, Labrador, and are set to have a fundraiser to support the work of community centres. Actor Mary Walsh—who emptied her freezer to help feed the neighbourhood during Snowmageddon— has signed on as a long-term volunteer.

In turn, Walsh has called on her TV character, Mrs. Eulalia, to energize people to support the cause. You can see what Mrs. Eulalia has to say about it all right here.

“If we don’t come out of this different, we’ve missed the boat,” says Hickman. “A small group of people can’t get to live their lives at the expense of everyone else.

“I hope the arts and cultural sector can transform who we are as a people. We can shine a light on the human condition. I consider [the opera company] to be a community organization with stakeholders. What is the community not getting that it needs? We are used to taking care of each other. We need to do this now as a planet.

“Nobody can get left behind so someone else can have more things.”

“I think artists are going to be focused on how they are going to be moving forward. There’s less room for pure entertainment, and more room for politics in art,” says Manuel.

“We’ve repeated historical patterns. Serious shit goes on when we’re not paying attention. I see my role as using my voice without turning people off. There’s a lot of history in puppetry about speaking truth to power. As an artist, I have to use my skills to present this to my community and to provoke a dialogue about a way forward.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.